- Home

- Mary-Kay Wilmers

Human Relations and Other Difficulties Page 3

Human Relations and Other Difficulties Read online

Page 3

In tributes to politicians the voice that is heard is not God’s but his viceroy’s, the Times leader writer. (It can also be detected, under the present editor, William Rees-Mogg, in long and thoughtful commemorations of English Catholic dignitaries.) In the case of minor politicians odd remarks give away the identity of God’s view and that of the Times. Maurice Edelman, for instance, ‘had long ceased to be enamoured of the left or Russia’ – ‘enamoured’ would not have been the word used had the attachment been thought suitable. But when statesmen (English or foreign) die their obituaries are as much a political statement as a tribute to their achievement. De Valera, though praised for his patriotism, was scarcely praised at all: ‘There was a bleak integrity and refusal to count the cost about many of his actions that was in apparent contradiction to the transparent opportunism of others.’ Franco, on the other hand, got off lightly in an obituary anxious to let bygones be bygones, to honour him for making Spain a respectable member of the Western alliance and to defend him from attacks made by less moderate opponents of the regime. The presence on the page of four photographs of the great ‘dictator who gave Spain a period of law and order’ indicated a fairly unambivalent celebration.

Even less ambivalent was the commendation of Ross McWhirter, ‘champion of individual freedom’. Had he died in his bed, he might have been commemorated as a ‘controversial’ figure who edited The Guinness Book of Records. As it was, murdered by the IRA, he was portrayed, by someone with views not unlike those the Times columnist Ronald Butt sometimes expresses, as a hero in an unheroic time: ‘He was, and it is curious that it has to be said, a man of unfashionable cut and cast of mind … He was not just a talker content to grumble and rail, he was a doer; he acted.’ (The same could be said of the ‘vociferous and intimidating minority’ against whom his doing was done.) It was incongruously left to the Times sports correspondent, who at any other time might have written the obituary, to add that his ‘political views sometimes seemed extreme’. There is nothing new in this editorial interest. In the past people have failed altogether to get a notice because the Times didn’t like their opinions; while Chamberlain’s obituary was written, probably by Geoffrey Dawson himself, with striking political bias. He was said, for instance, to have been bitterly attacked by the Labour Party for ‘appearing to condone the Italian military action against what they chose to call “democracy” in Spain’. As for appeasement, it had ‘failed with honour’: ‘By exhausting every possibility of peace before entering upon war Chamberlain had at least brought Britain into the conflict with clean hands.’ An air force would have been more useful.

The tribute to Chamberlain was exceptional in saying nothing about his character: perhaps the conflict between the time and the Times made it difficult for the writer to find a form of words acceptable to both sides. Not that obituarists are discouraged by problems of that kind: only Oscar Wilde himself (for whom ‘death soon ended what must have been a life of wretchedness and unavailing regret’) was more fond of paradox than the common or garden obituary writer. Poor Mrs Humphry Ward: ‘As inspiration declined, her technique improved, and as her special message grew less her output grew greater.’ Sir Kenneth Pickthorn, we’re told, had a ‘talent for repartee and a capacity for sustained logic which made him invincible even when he was unpersuasive’. In less artful hands, antitheses – in fact, excuses – are set up that even Sir Kenneth’s logic could not have sustained. ‘He was inclined to see the issues in terms of black and white but this in no way detracted from his kind and helpful nature’ – why should it? ‘The experts might not always agree with him but his clear expression and often entertaining manner was a valuable contribution to our understanding of human evolution’: his writing was worthless but readable. On the one hand a vice, on the other a virtue, but rarely the virtue of vices or vices of virtue: ‘Laconic, penetrating – at times acid in his comments he never gave offence.’ Nor even the vices of vices: ‘His often disconcertingly blunt manner sometimes gave a false impression of rudeness and insensitiveness.’

Similarly, the deceased is never what he seemed to be if what he seemed to be was unattractive: ‘Although he cultivated a somewhat grandiose exterior and formidable manner, he was at heart a complex, sensitive man.’ If so-and-so’s manner is pompous, he is in fact very jolly; if his manner is light-hearted he is in fact very serious. The historian J.E. Neale seems to have taken in both sets of contradictions: ‘Behind the warm genial personality was a tough conscientious scholar’ and ‘beneath his Lancastrian bluntness and moments of supreme tactlessness … was a profound humility in the presence of historical scholarship and the mellow generosity of a great scholar.’ In this way all qualities are neutered and nothing really bad has been said about anyone. If a man is widely disliked, he has ‘no concealment, no dissimulation, no artifice, no humbug’; if a man is eager to get on, it is for the sake of something wider, for he is ‘without personal ambition’; a ‘large and influential landowner’ is ‘a very humble man’; a man renowned for the bizarreness of his dress is said to be ‘devoid of interest in personal appearance’.

It’s all a ruse, of course, a way of slipping unkind things which are also sometimes called the truth into the context of an encomium. How important is this truth-telling function where it concerns people’s character, and how often does it become a liberty? Very often, would be the stern answer; and although the taking of liberties is a large part of what makes obituaries a pleasure to read it could more easily be justified when the values of the people who read them were less disparate. Besides, the truth about people’s characters and private lives isn’t told in all sorts of ways, the most obvious of which is that homosexuality is never mentioned. Or is told of some but not of others. In Constance Malleson’s obituary there was no reference to her relationship with Bertrand Russell: Utrillo’s devoted seven inches to the irregularities of his life and three to his work. Or is darkly hinted at but never revealed: the nature of Oscar Wilde’s offence; or ‘the emotional wound, so long unhealed’ but for which Eliot’s ‘poetry might well have been more genial, less ascetic’. Sometimes what might appear to be the truth turns out not to have been the truth at all: L.S. Lowry’s obituary portrayed him as an inarticulate recluse – a few days later someone who seemed to know him well described him as ‘one of the most fluent conversationalists one has been privileged to encounter’. And sometimes the truth seems to be a flimsy disguise for malice. One doesn’t have to be Alastair Forbes or a fan of Cyril Connolly’s at all to feel some unease on reading that he was ‘a notable victim in the lists of love’.

Writers are particularly liable to malicious obituaries. Perhaps because they are not protected by a professional parti pris; perhaps because they are considered, as Cyril Connolly probably was, to have placed their lives in the public domain. A more likely reason, however, is that their obituaries are the work of other writers who review their lives as they would their books and have little inhibition in passing judgment on either, or in using their lives in evidence against their books. Ezra Pound’s obituary, described by Janet Adam Smith in an angry letter to the Times as a ‘mishmash of literary opinion and personal speculation’, launched into an opaquely detailed account of his private life from which it soon followed that he was a ‘major craftsman and an extraordinary energy but not a major human poet’. The truly remarkable aspect of the piece, however, was its opening attack on Eliot. Pound died not long after the publication of the draft manuscript of The Waste Land and someone evidently thought his obituary the right occasion to settle some old scores. The draft of The Waste Land, this person said,

reveals that Pound, whom one tends to think of as coarse and boisterous where Eliot was refined and reticent, had a kind of essential innocence and fastidiousness that was denied to his friend … From Louis Zukofsky to Alfred Alvarez, many of Pound’s best friends (to use the horrible old joke-cliché) were Jews. The young Eliot of The Waste Land period seems, about Jews, to have had an almost insane physical nau

sea. If The Waste Land had been published in its first draft, it would have been a document of, not exactly madness, but very distressing psychological instability. Pound was the main instrument in turning it into an enigmatic near-masterpiece. His own anti-Jewishness was simplistic and ideological, based on ideas about usury. Jews tend to be open-minded and intelligent, and Pound tended to like individual Jews. Eliot was right to salute him as ‘il miglior fabbro’ and might also have saluted him as a less obsessed and tormented soul.

Still, it was nice of the writer to put in a good word for the Jews.

Rex Stout got an enthusiastic obituary recently and Agatha Christie’s, though coolish (‘she was not, in fact, a particularly good writer’), was not unpleasant. Thornton Wilder’s obituarist wouldn’t quite say whether he agreed with the public (who liked him) or the critics (who didn’t), but gave the public the benefit of the doubt. D.H. Lawrence, however, queered his pitch:

There was that in his intelligence which might have made him the writer of some things worthy of the best of English literature. But as time went on … he confused decency with hypocrisy, and honesty with the free and public use of vulgar words.

And so he ‘missed the place among the very best which his genius might have won’. Eliot, ‘OM and Nobel Prizeman’ (sic), did all right in his own obituary: given the OM it could hardly be otherwise. And if there was ‘that’ in his work which did not please the school matron who sits at the right hand of God, it turns out that it was only an affectation of the kind that intellectuals are easily taken in by: The Waste Land’s

presentation of disillusionment and the disintegration of values, catching the mood of the time, made it the poetic gospel of the post-war intelligentsia; at the time, however, few either of its detractors or its admirers saw through the surface innovations and the language of despair to the deep respect for tradition and the keen moral sense which underlay them.

When Joyce died – ‘an Irishman whose book Ulysses gave rise to much controversy’ – Eliot wrote to the Times complaining that the obituary had been written by someone quite unsuited to the task. Not that whoever it was had not tried to be fair: ‘In person Joyce was gentle and kindly, living a laborious life in his Paris flat, tended by his devoted, humorous wife’; a pity, though, that ‘the appreciation of the eternal and serene beauty of nature and the higher sides of human character was not granted to Joyce.’

The Times declined to print Eliot’s letter, which was published in Horizon. ‘The first business of an obituary writer,’ Eliot said,

is to give the important facts about the life of the deceased, and to give some notion of the position which he enjoyed. He is not called upon to pronounce summary judgment (especially when his notice is unsigned), though it is part of his proper function, when his subject is a writer, to give some notion of what was thought of him by the best qualified critics of his time.

Traditionally Times obituaries have not confined themselves to the important facts nor refrained from delivering summary judgments – that is part of their interest and their charm. And however numinous anonymity makes them seem, they often deliver the wrong summary judgments – but that too is part of their eccentric, English charm. At their very best they are short biographical essays, offering something more than the facts – an account of the life that was led, of what it meant to be that person as well as to do what he did.

It has been customary for Times obituaries of the very eminent to be reprinted in the DNB. And in 1975 for the first time a select ion of obituaries was published in volume form; ‘a contemporary dictionary and reference book of international biography’ was how Philip Howard described it in the Times.* But the average obituary is quite different from an entry in a dictionary of biography, its function being not just to assess achievement and assign merit but to honour someone who may well receive no further honour. The inhabitants of a perfect world, Lionel Trilling said in a reference to Morris’s News from Nowhere, might feel that ‘being a person is not interesting in the way that novelists had shown it to be in the old unregenerate time.’ Hugessen wasn’t a great man and wouldn’t rate a place in a biographical dictionary, but his obituary was mindful of the interestingness of being that person, with those limitations, in the old unregenerate pre-scrambling time.

*Obituaries from the ‘Times’, 1961-1970.

Next to Godliness

Pears’ soap is a venerable English soap: the first to proclaim itself gentler than any other and the subject of one of Britain’s first and most celebrated advertising campaigns. It is oval, the colour of candied orange peel, and translucent. ‘Delicately perfumed with the flowers of an English garden’, according to the company publicity handout; but what it brings to mind is not the flowers of the garden so much as the old domestic institutions – shallow baths in icy boarding-school bathrooms, and coal fires in the nursery. The advertising campaign began some hundred years ago, when Mary Pears married a young man named Thomas Barratt, whom she had met at an academy of dancing and deportment. Barratt joined the Pears family business, and turned out to be an advertising genius.

In 1897, Pears, under Barratt’s direction, published a one-volume encyclopedia – Pears’ Shilling Cyclopædia. It was the noonday of the British Empire, the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The encyclopedia quickly earned its place in Victorian households between the family Bible and the works of Dickens. Thousands of copies were sold in British possessions overseas. The Times of London said, ‘It is neither inadequate nor inaccurate,’ which wasn’t altogether accurate; an Irish convict said that it was ‘the most popular book in the prison library’. Pears claimed in their advertisements that nothing had ‘ever before been issued equal to it at twenty times its price’. It is now in its 88th edition and still flourishing.

The business was started by Andrew Pears, Mary’s great-grandfather, who set up shop in London in the year of the French Revolution and soon became a prosperous manufacturer of good soap for the better classes. But by the time Thomas Barratt joined A. & F. Pears, Ltd, in 1865, the Industrial Revolution had taken place and the better classes had ceased to matter so much, commercially speaking: wide promotion could achieve wide sales among all sorts of people. No one saw this more clearly than Barratt, who boasted that he would advertise as no soapmaker had advertised before. There aren’t many tricks of advertising as it is now practised that Barratt didn’t think of. He persuaded the president of the Royal College of Surgeons to tell the world that his soap was uncommonly safe and healthy, and the beautiful Lillie Langtry to say that Pears’ soap was the only soap she used. On a trip to New York, he stuck his foot in Henry Ward Beecher’s door and got him to write the following encomium:

If Cleanliness is next to Godliness, soap must be considered as a ‘means of Grace’ – and a clergyman who recommends moral things should be willing to recommend soap. I am told that my commendation of Pears’ Soap some dozen years ago has assured for it a large sale in the US. I am willing to stand by any word in favour of it that I ever uttered. A man must be fastidious indeed who is not satisfied with it.

In order to spread the good man’s word, Barratt bought the entire front page of the New York Herald – something that had never been done before. In the first eighty years of Pears’ existence, a total of five hundred pounds sterling was spent on advertising its soap; within a few years of Barratt’s joining the firm, the annual advertising budget was in the order of a hundred and twenty-five thousand pounds. He imported a quarter of a million French ten centime pieces – which at the time were accepted as the equivalent of an English penny – and put them into circulation with the name ‘Pears’ stamped on each one. An Act of Parliament had to be passed to get them out of circulation.

In his own way, Barratt became a patron of the arts, going to art exhibitions to buy up potential advertising material. One of his most successful ads derived from a painting he saw at an exhibition in Paris. In one corner of the picture, a squalling baby was leaning out of a tin bath

trying to grab a rubber toy just out of its reach. Barratt bought the right to reproduce the baby and the bath, substituting for the toy a bar of Pears’ soap. His caption – ‘He won’t be happy till he gets it’ – straightaway became part of the stock-in-trade of music-hall comedians, cartoonists and politicians. Another, more sweetly English painting brought Barratt’s advertisements their greatest fame – and, thanks to the ad, there was for a time no more popular English work of art. The painting was ‘Bubbles’, an 1886 portrait by Sir John Millais of his grandson watching a soap bubble he had just blown through a clay pipe. The Illustrated London News owned the copyright, and for twenty-two hundred pounds Barratt acquired the right to use it. After Millais’s death, in 1896, it was said that he had not liked the way Barratt exploited his work, and the issue was heatedly argued in a series of letters to the Times. Millais’s son, in a biography of his father published in 1899, said that Millais was ‘furious’ when Barratt showed him the ad. Barratt did not agree; according to him, Millais had called it ‘magnificent’.

Encouraged by his generous words [Barratt wrote to the Times], I spoke of the advantage which it was possible for the large advertiser to lend to art – he could give a very much greater publicity to a good picture than it could receive by being hung on the walls of the Royal Academy. Sir John Millais, with alacrity, appreciated that idea, and when I stated the extreme difficulty experienced by those desirous of advertising by means of the graphic art, to induce good men to paint pictures, Sir John, taking his pipe from his mouth, said, ‘What … nonsense! I will paint as many pictures for advertising as you like to give me commissions for.’

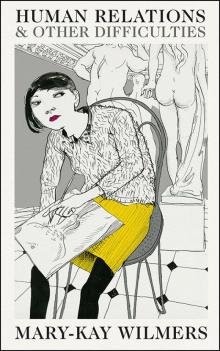

Human Relations and Other Difficulties

Human Relations and Other Difficulties