- Home

- Mary-Kay Wilmers

Human Relations and Other Difficulties

Human Relations and Other Difficulties Read online

Human Relations and Other Difficulties

Human Relations and Other Difficulties

Mary-Kay Wilmers

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Profile Books Ltd

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London wc1x 9hd

www.profilebooks.com

Introduction copyright © John Lanchester 2018

All essays copyright © Mary-Kay Wilmers in year of first publication unless otherwise stated

Details of first publication for each essay appear on page 248.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

All reasonable efforts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if notified in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 523 3

To Andrew O’Hagan who had the idea and John Lanchester who made it happen

Contents

Introduction by John Lanchester

I Was Dilapidated

Civis Britannicus Fuit

Next to Godliness

The Language of Novel Reviewing

Narcissism and Its Discontents

Death and the Maiden

Divorce Me

Patty and Cin

Hagiography

Vita Longa

Sisters’ Keepers

Fortress Freud

Lady Rothermere’s Fan

Quarrelling

Promises

Nonchalance

Attraction Duty

My Distant Relative

Brussels

What if You Hadn’t Been Home

Peter Campbell

Flirting Is Nice

What a Mother

Acknowledgments

Credits

Introduction

In the 1956 edition of the Badminton School magazine, the Literary Club’s end of year report describes a focus on Irish drama, concentrating on the work of Synge, Shaw and O’Casey. Unfortunately, ‘exams of all sorts have prevented us from having as many meetings as we would have liked,’ but things picked up when they were over. ‘At the end of the Summer Term we organised a literary competition,’ reports the head of the club, ‘ostensibly in aid of refugees (there was an entry fee) but with the surreptitious motive of extracting literary works for the Magazine.’

That is the first surviving piece of writing by Mary-Kay Wilmers, and the activity with which it ends – extracting literary works from reluctant writers – has been the central focus of her working life for more than fifty years. She began doing it at Faber, in the days when the dominant presence at the company was T.S. Eliot. (There was a hierarchy to the way his colleagues referred to him: seniors called him ‘Tom’; underlings ‘the GLP’, for ‘Greatest Living Poet’.) She left Faber to go and work with Karl Miller at the Listener, went to the Times Literary Supplement, then co-founded the London Review of Books in 1979. She has been sole editor of ‘the paper’ – as it is always known in LRB-speak – ever since 1992. That is a lot of not-so-surreptitious extracting of pieces. (‘Pieces’, incidentally, is another example of LRB-speak: the things it publishes are always known not as reviews, essays, or articles, but pieces.)

Alongside all this, though, there has always been another version of Mary-Kay, and that is Mary-Kay as writer. When I first met her, after I started out as the LRB’s editorial assistant at the beginning of 1987, writing was more central to her work and indeed to her identity than it is now. ‘I don’t go on about it,’ she once said, waving away a cloud of smoke from her cigarette, ‘but that’s my main thing.’ She meant writing. Both parts of that were true: she didn’t go on about it, but it was. She put a lot of effort and energy into her writing, and always had a piece on the go to the side of her editorial work. She had written for Ian Hamilton’s New Review (her piece on obituaries is collected here) and had had a personal thank-you note from William Shawn after he published her piece on encyclopedias in the New Yorker (that piece is here too). She would certainly have written more for Shawn if editing her own magazine hadn’t got in the way.

Everybody who reads the LRB is deeply in her debt for the heroic contribution she has made to the culture as an editor. Some of us have a small accompanying regret, though, and that is that she hasn’t done more writing along with it. We get the reasons: the main one is to do with time. But we miss those unwritten pieces nonetheless. She is one of the LRB’s most distinctive contributors, with a tone and affect that isn’t quite like anyone else’s. A few of the pieces I read over and again, back when I first knew Mary-Kay, trying to work out what it was about them that was different. It was a long time later that I found the key, in a remark that Janet Malcolm made about Joseph Mitchell: she used to marvel, she said, at how he managed to get ‘the marks of writing’ off his work. Mary-Kay’s pieces are like that: they don’t smell of writing.

The pieces in this book don’t read as effortful, but that’s misleading. Mary-Kay works as hard at her writing as anyone I know. She is not the kind of writer who does things off the top of her head: I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone who takes more notes. She once reported her son Will, then about 14, saying she was ‘copying out the book’ – it was funny because he didn’t mean it as a joke, and also because, as she put it, ‘that about sums it up.’ The end product is clear as vodka, a clarity which is all the more striking since Mary-Kay is often in two minds about things. In her pieces she specialises in seeing both sides of a question; for instance in ‘Narcissism and Its Discontents’, she sees both the ways in which it must be quite nice to be a committed narcissist, as Jean Rhys was, and also the ways in which a lifelong focus on your own looks is certain to end in misery. Freud’s greatness comes through in her essay on Janet Malcolm, and so does his pettiness; the interestingness of psychoanalysis as a world, and the cultish limitations of its world-view. Other pieces show us both sides of the question on subjects as diverse as novel-reviewing, Patty Hearst and Ann Fleming. She is never more translucent than when she is ambivalent. It’s an unusual talent.

The Fleming review also shows off one of Mary-Kay’s great gifts, which is for apt quotation. That is one of the reasons she ‘copies out the book’, to home in on the most relevantly quotable part of it. In the case of Fleming’s letters, the whole piece (indeed the whole book) can be boiled down to one single incident during a rowdy party. Various aristocrats were swearing uncontrollably and, as Fleming recounted in a letter to Evelyn Waugh, Deborah Devonshire turned to Roy Jenkins to intervene:

‘Debo said to Roy Jenkins: “Can’t you stop them by saying something Labour?”’ – ‘but this,’ she says to Waugh, ‘is something Roy has never been able to do.’

That’s not just a book summed up, it’s a whole world.

Rereading these pieces, there were many things I remembered and one big thing I didn’t. It is great fun to bask in the aphoristic asperity that is one of the big pleasures of her writing. On Jean Rhys: ‘Reluctant to make any move unassisted by fate, she simply waited for men to arrive and then to depart.’ On Henry James senior: ‘He was ambitious in his expectations of his children, but what he required of them w

as intangible: neither achievement nor success but “just” that they should “be something” – something unspecifiably general, which could loosely be translated as “interesting”.’ ‘Heroines endear themselves by their difficulties and until the SLA kidnapped her Patricia Hearst’s only difficulty was that she was a bit short.’ On Marianne Moore and her mother: ‘They lived as if they didn’t quite know how to do it.’

The thing I hadn’t noticed, though, and which came as a surprise reading Human Relations and Other Difficulties in one go rather than as a series of pieces over many years, was that there is a secret thread to the collection. After the first four pieces, all the essays are from the LRB, and almost all of them are about women. Mary-Kay’s great concern is not so much gender as the relation between the genders, and especially the effect on women of men’s expectations, men’s gaze and men’s power. ‘It’s a matter of expectations and how they can be met,’ she says in discussing Jean Rhys, and that is true for all the lives she discusses. Women’s reality is framed by men; it is men who have all the important agency in the world; women’s agency is limited by men, is determined principally by the way they want to be perceived and defined by men. The world of her pieces is about women’s lives in a man’s world. As she says in a piece from the early 1990s:

I didn’t do consciousness-raising with my sisters in the late 1960s. I was married at the time and it seemed to me that if my consciousness were raised another millimetre I would go out of my mind. I used to think then that had I had the chance to marry Charles Darwin (or Einstein or Metternich) I might have been able to accept the arrangements that marriage entails a little more gracefully.

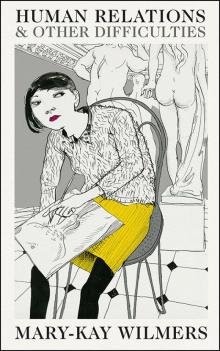

Of course, it wouldn’t be a collection of pieces by Mary-Kay if there wasn’t evidence that she was in two minds about things. The warmest piece in Human Relations and Other Difficulties is about a man, Peter Campbell, the LRB’s longstanding designer, artist, and a presence who was ‘always at the heart of the LRB’ from its founding until his death in 2011. In 1992 Mary-Kay remarked to Peter, ‘Why is it always men painting naked women? Why is it never women painting naked men?’ The image on the front of this book, which was used as an LRB cover, is Peter’s response to the question, and is also a sly opportunity to slip in a portrait of Mary-Kay. It’s a picture which captures not just Mary-Kay’s remark about art but also Peter’s vision of Mary-Kay as an artist with her back turned, watching, judging, and covertly telling her side of the story.

John Lanchester

I Was Dilapidated

‘What did you have?’

‘A boy.’

‘Congratulations.’

If your first child is a girl I’m told people say: ‘How nice.’ How nice. My child is of course wonderful but I am also – embarrassingly – slightly proud that he’s a boy. Childbirth is full of such pitfalls, where the wish to be congratulated overrules common sense. I don’t find the standard notion of the good wife very compelling. But the pressure to be ‘a good mother’ according to the prevailing definitions is practically irresistible. I can keep my head when David Holbrook, in his most recent outburst against ‘art, thought and life in our time’, warns that it is a failure in mothering that produces intellectuals and other pornographers: it’s less easy to steer a clear course through all the varied strictures of the psychoanalysts themselves.* Worse still, it’s by no means adequate to try to behave like a good mother, because that involves an act of will: goodness itself is supposed to emerge. Before Bowlby, you only had to keep your children clean and set a decent moral example. Now ordinary selfishness is thought somehow to be expelled in the moment of delivery, or sooner: it’s selfish, you’re told by the masked figures gathered expectantly around you, if you can’t manage without forceps. Better mothers don’t need them.

It’s logical enough. Since having children is a matter of choice, or, some might say, a deliberate self-indulgence, there is an obvious obligation to do the best one can by them. What worries me is that logic is so seldom invoked: naturalness, spontaneity are the mots d’ordre. Which hardly takes into account the fury one may oneself feel at an infant who rages when he should be feeding, and indeed would like to be feeding if only he could stop raging. On the other hand, I find little consolation in the knowledge that if on these occasions I were to act on what I take to be my ‘natural’ inclination and batter my baby, the law would return a verdict of diminished responsibility and I wouldn’t go to prison: I’d rather go to prison. But why is ‘natural’ taken to be a synonym for ‘good’?

I accept that much of what I’m saying could be ascribed to puerperal paranoia, with the proviso that the form the paranoia takes derives from current attitudes. According to New Society it’s a rare father who can change his child’s nappy. Until children reach an age where they can be reasoned with, the only notices fathers get are good ones. I like changing my son’s nappy – foolish of Freud not to pay more attention to Jocasta’s part in the relationship. But sometimes I wonder why I’m thought to have a special scatological aptitude. People ask me eagerly if I enjoyed feeding him myself: I didn’t. The first weeks of feeding were often very humiliating (I’ve never felt so sympathetic to men’s fears of impotence), particularly when the humiliation was repeated every three hours. Now I’m proud of being a self-sufficient life-support system – farmer, wholesaler, restaurant and waiter – but initially I felt as if I’d been pinned to a conveyor belt serving a remote and self-obsessed baby. Eager to cram something into my own mouth, I took up smoking; a friend in the same situation started biting her nails.

I’d read plenty of articles about mothers getting upset when their children grow up and leave home, but it seemed a bit much to resent his leaving the womb. Still, he’d been mine before and now I was his. I couldn’t sleep without his permission, I ate for his sake rather than mine, I felt guilty if I took an aspirin, and if I was late home it was as if I was capriciously denying him his means of existence. If I got upset his provisions were threatened, and if the provisions were threatened I got upset. In addition, he was admired and I was dilapidated. Childrearing manuals have a section on the importance of the mother making the father feel that he too has a relationship with the new child – but it was six weeks before I felt I had a relationship with the child myself. My husband was the supervisor, a position which left him free to enjoy the child. ‘For Dockery a son,’ I thought, with uncharitable memories of Larkin’s poem.

In short, I didn’t get depressed because I couldn’t cope, as the books said I might: unless things are really bad you can always grit your teeth and make yourself cope. I got depressed because instead of maternal goodness welling up inside me, the situation seemed to open up new areas of badness in my character. Perhaps paediatricians believe in the power of positive thinking: I’ve always found it harmful. There’s nothing magical about a mother’s relationship with her baby: like most others, it takes two to get it going. Once the baby begins to enjoy feeding, once it starts responding to situations in a way that you can understand and smiling huge smiles and playing and ‘talking’ and watching, then you begin to feel the famous warm glow. Before that you’re on your own, and the least ‘natural’ thing in the world is suddenly to change your character.

*Sex and Dehumanisation by David Holbrook.

Civis Britannicus Fuit

If the Times is still in any sense the institution it once was, it’s because of its letters page and its obituary column: the voice of the people (some of them) and the voice of God, a benign, very English God, or schoolmaster, not much interested in foreign fiddle-faddle but ingenious in drawing up the end-of-term reports:

Hugessen’s career was a successful one and he was fortunate in never having had to meet a situation demanding more of him than he had to offer; for he had his limitations, of which he was charmingly conscious and which he openly admitted. He had not, for instance, the kind of compelling personality which can influence men or events. Indeed, there was something boyish, almost ungrown-up about him: not for nothing did

the nickname ‘Snatch’, conferred on him at school, stick to him all his life.

Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen was British ambassador to Turkey from 1939 to 1944. The book Operation Cicero described how his Albanian valet regularly photographed secret documents sent to him by the Foreign Office and passed them on to the German Embassy. ‘It is proof of the high regard felt in the Foreign Office for Hugessen,’ his obituarist noted, ‘that this strange affair did not affect his career.’ And it is proof of the high regard God was once thought to feel for Englishmen that on Hugessen’s death his many limitations were celebrated over three columns. But then Hugessen belonged to an era when heaven smiled on Englishmen, especially Englishmen of average ability; and Hugessen had ‘a mind which instinctively eschewed complexities and so saved him from the pitfalls which, especially in dealings with clever foreigners, beset the path of the over-ingenious intellectual’.

Hugessen died in 1971 at the age of 84, but his obituary would have been written years earlier, possibly by someone who died long before him. If one compares current obituaries with those that were published twenty years ago what one notices first is that the notion of a state of grace – civis Britannicus fuit – has yielded to the more stringent doctrine of justification by works. In part the difference is the consequence of a policy decision. When William Haley became editor of the Times in 1952 he decided that inclusion in Debrett, or even Who’s Who, was no longer in itself sufficient grounds for an obituary: people were to be selected on the basis of their achievement. And although inclusion in Who’s Who is still sometimes considered an adequate reason, it too has changed.

Before Haley’s decree took effect members of the aristocracy who had done nothing much beyond providing fellowship in the hunting field and conviviality at the dinner table, unmemorable members of the armed services and the Church (‘he found a congenial task in looking after the Guardsmen stationed in the castle’), as well as anyone who was thought to be charming in charmed circles – friends of friends, public schoolmasters, an archbishop’s wife’s secretary – could all count on making some kind of splash when they died. Now they stop a hole at the bottom of a column.

Human Relations and Other Difficulties

Human Relations and Other Difficulties